Memoirs

Working on the Royal Portraits.

Ideas come true.

Recollection of artist Alexei Maximov, March 2011.

I worked on “The Royal Portraits” together with Leonid Efros, but it wasn’t our common work; we created two separate series. I was focusing on enamel miniatures, whereas Mr. Efros was doing easel painting. A number of events —exhibitions, publications, and coincidences—led us to London, and later to The Hague and Oslo. Let me tell you the back-story first.

Enamel portraits

Podolsk, near Moscow, in 1979 became the first city to showcase our work, mostly historic enamel portraits. Romantic portraits of nineteenth century poets and handsome generals in neat full-dress uniform were perfect for enamel painting. Historic portraits were, of course, a good thing to do, because things became a lot more complicated with contemporaries. There were some orders to make VIP portraits with numerous decorations and medals, but these images weren’t inspiring. I was afraid that starting such work would lead to disaster; for example, the enamel would burst in the oven.

Our main breadwinner was Peter the Great; we made his portraits with pleasure. We were sure that each work would go to either a museum or a private collection. Besides the officially allowed images of the Emperor, other czars were permitted, but only from a distance, on horseback, for example. We used to call such images “Horsemen.” A lot more portraits were allowed on miniatures than on easel painting. After my personal exhibition at the State Literature Museum In 1979, they decided to buy my portraits of Anna Akhmatova and Andrei Bely for their collection.

A.Maximov, Portrait of

D.Venevitinov

L.Efros, Portrait of

General Khrapovistky

Exhibition at the Kremlin Armoury

In early 1990, after an exhibition at The Dostoevsky Museum in St. Petersburg, I brought Mr. Efros’ and my works to Moscow at the invitation of the Kremlin Museum. I assumed they wanted them for private purchase (the museum already had one of my works in its collection), but it turned out that the academic board of the Kremlin Museum had been looking for contemporary painters for a series of private exhibitions they were organizing. They had Fabergé’s offspring from London, Ananov from St Petersburg, Gilbert Albert from Geneva, and others, but they didn’t want to open the series with any of these artists. In May 1990, therefore, Mr. Efros and I were invited to showcase our works in the Kremlin Armory. The exhibition opened in December 1990.

During the exhibition, the Kremlin Museum did acquire some of my works for its collection. I later signed a contract to make a portrait of Carl Fabergé for the jubilee exhibition in 1991.

I.A. Rodimtseva, A.A. Maksimov, L.M. Efros on the opening

of the exhibition. the Kremlin Armoury, 1990

Exhibition at the Kremlin Armoury

"The World of Fabergé"

My portrait of Carl Fabergé was showcased in the central hall next to the main display of the exhibition — the egg called “The Moscow Kremlin.” After Moscow, “The World of Fabergé” was showcased in New York, Toronto, and Sydney. This exhibition was quite well received, like its predecessor, “The Christmas Fabergé Eggs,” which was organized by the Kremlin Museum and Henry Forbes and was, of course, of worldwide renown. Quite naturally, Sir Geoffrey de Bellaigue, Surveyor of the Queen’s Works of Art for Elizabeth II and Director of the Royal Collection, knew about it. I don’t know in which city he visited the exhibition, but I saw its catalogue on a table in his office. Since the catalogue contained my work, we “knew” each other before meeting in person.

The central showcase of

"The World of Faberge"

exhibition. The Moscow

Kremlin Museums

Portrait of Carl Faberge,

1991., A. Maximov

Conversation in the kitchen

The esthetic of the past was still alive in the early 1990s. Over a cup of tea, Mr. Efros and I talked about philosophy, art, and projects for the future. After the Kremlin Armory exhibition, we knew we needed to do something special, and the idea of painting current European monarchs was born, right there in the kitchen of Rimma Yunosheva. Mr. Efros was sure that was what Rimma had in mind when she said, “After such an exhibition, it’s time you painted the queens!” Perhaps it was indeed time for that.

How the idea came true

Irina Rodimtseva, the Kremlin Museum’s director, was very supportive of our plans. She wrote a letter to Sir Geoffrey (she had kept in touch with him after the Christmas Eggs exhibition) and helped us apply for our UK visas. We had a contract with the Museum for a series of English portraits. All the circumstances were favorable.

We went to London in November 1991 and got acquainted with Vitaly Lukyantsev, Russian Embassy Cultural Advisor, who helped us enormously. The political situation in Russia was quite tense, and Mr. Lukyantsev had to take several decisions on his own. He accepted the risks and introduced us to Sir Geoffrey.

Sir Geoffrey, in his turn, introduced us to Sir Kenneth Scott, Queen Elizabeth II’s private secretary. Sir Kenneth explained that the Queen could sit for a portrait in some five years…at the very earliest. He suggested that we meet the Queen’s photographer and gave us his business card, promising to put in a good word for us. Making the Queen’s portrait from photos was of no interest to us at all, however, and Sir Kenneth knew that. To soothe us (and perhaps his conscience), he promised, “I’ll do my best.” And it turned out that his best was very good indeed. In two weeks’ time, we received a message from him, and the Queen’s sitting took place in March 1992. In fact, this was a sitting arranged for Theodore Ramos, the Spanish painter, who allowed us to share his time in the room.

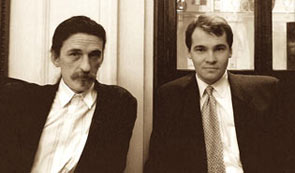

Meeting in the Gorbachev′s Residence

With Alexander Konanykhin. Vienna, 1993

According to the agreement with the Moscow Kremlin Museums, we could expect the payment only after completion of all work. However, the enamel miniatures take a lot of time and have to be framed (ideally in gold) and well-presented. We didn’t know how long we would have to spend in London (a week? a few months?), and London is not an inexpensive city. Something had to be arranged. The solution was found by my father, when we talked in his house near Moscow. He thought that the simplest solution is often the best one. He picked up Pravda newspaper from the table, unfolded it and on the second page we saw a full-page ad of the Russian Exchange Bank. “Write to the president of this bank” he said, “after all, you have a very interesting project.” I did, and to my surprise, my letter worked. The bank representative called my father’s number (mobile phones didn’t yet exist), and said that he’d send over a car. We agreed on the date and time, though I was not sure whom I’d be meeting with.

A couple days later, in a former state residence of Gorbachev (so-called “Residence Number One”) I met with Alexander Konanykhin, the president of the bank. The story of Alexander and why we were meeting in the Gorbachev’s Residence would require a separate narration. Here it’s enough to say that very soon the Moscow Kremlin Museums signed an agreement with Konanykhin, in which he pledge financing of the “Royal Portraits” program. The work related to the British series of portraits and then on the portrait of the Queen of the Netherlands was made possible by his financial support.

Dress suit

I usually worked in a sweater and leather jeans that weren’t suitable for this occasion. I wasn’t used to wearing a dress suit while working, and I didn’t like wearing formal clothes. Coincidentally, however, I had a dress suit, sewed in Paris in 1890. It was in good condition and suited me perfectly. I had a shirt designed by Irina Blau in St Petersburg and a silver watch belonging to Pavel Bure’s grandfather. I also got a wonderful coat, ideal for London’s March weather.

The Queen's sitting at Buckingham Palace

Court Artist Th.Ramos and

V.Lukyantsev, 3 March 1991

On his website, Mr. Efros recalls his conversation with the Queen, and a little fox he saw in a nearby park. Frankly, I don’t remember that. Recollection is, no doubt, a subjective phenomenon. What I remember vividly is the crowd at the entrance gate of the palace. I remember the Queen asking her secretary, "Who are all these people? What do they want?" I remember Sir Kenneth's reply: "These are teachers asking for an increase in their pay."

The entrance gate as seen from the Yellow Drawing

Room

It was Mr. Lukyantsev who was most engaged in conversation with the Queen. He was so skillful that the Queen took interest in everything he had to say.

The sitting was in the Yellow Drawing Room, where one detail moved me greatly: a small table with a basin, a water jug, and a soap dish. If a painter wanted to wash his hands, here was an improvised washstand. What courtesy!

Improvised washstand

The newspapers wrote about a unique historical event: it was the first time in history that the ruling English monarch had agreed to sit for Russian painters. In 1923, Elizabeth (the Queen Mother, then Duchess of York) and in 1949, Princess Elizabeth (now Queen) had sat for the Russian émigré painter Sevely Sorin, but neither had been a reigning queen at the time Sorin painted her.

This 1992 sitting lasted for almost two hours instead of the 40 minutes that had been planned. At our request, Mr. Lukyantsev told the Queen of our desire to paint Prince Charles and Princess Diana. At that time, the public knew nothing of the difficult situation in the Royal family, and the Queen acted as if she hadn’t heard the question. Later, however, she said, “It would be lovely to make portraits of the Queen Mother and Princess Anne. I shall talk to them about such a possibility.”

Honestly, I didn’t hear or understand all the conversation with the Queen. I was fully absorbed in my work; I wanted to accomplish as much as possible. I didn’t know about these additional sittings, therefore, until Mr. Lukyantsev told me about them on our way back to the hotel. Sure enough, in the same Yellow Drawing Room at Buckingham Palace, a week later, Princess Anne sat for us.

The Queen Mother

When I was studying English to pass my exam, I knew that in England there lived the matriarch of modern European monarchy, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother. She was 92 years old when she sat for our portraits. She remembered World War I clearly and had played a significant role in World War II, when she and her husband, King George VI, symbolized their nation’s fight against Hitler.

Before the sitting, I looked of some pictures at the queen mother, who looked brilliant for any age. No plastic surgery disguised the history in her wrinkles. Elegant and very feminine, she had a bright gleam in her eyes. She asked, “Would you like me to show you my favorite portrait?” Then she ran up the first floor, so quickly, to retrieve the work of Sorin, done when Her Royal Highness was 23 years old.

Her ladies in waiting gathered downstairs with us for a small reception. Her secretary presented us books about the Royal Family. Then she turned to her secretary: “I suggest that we drink some vodka with these Russian painters.” She loved the portrait that much.

“Drink some vodka” is easy to say, but the queen mother got a cup, whereas each of us got a big glass. I couldn’t drink a glass of vodka, but how could I refuse? I decided it was better to refuse, though, than to disregard my physiology. I hoped that no one would execute me and finished the glass only after the reception.

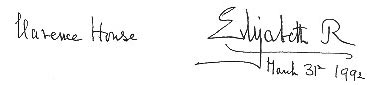

Signature on the original picture, 31 March 1992

Enamel miniature, gold

Enamel Miniatures

After all the work had been completed, I decided to show my portraits to Queen Elizabeth II. Sir Geoffrey agreed to meet me again, and I went to London. Sir Geoffrey could see the Queen without any advance arrangements, so he showed the miniatures to her the same day. I was pleased to hear favorable reviews and that I was free to exhibit or publish my work. My second personal exhibition took place in September 1994 at the Kremlin Armory, timed to coincide with the Royal visit to Russia.

With Sir Geoffrey, Director of the Royal Collection.

St James's Palace. London, 1994

The Netherlands

Huis ten Bosch. Hague,

March 1994.

In March 1994, after long negotiations between the Kremlin Museum and the Dutch embassy in Moscow, two sittings were arranged for me with Queen Beatrix. Mr. Efros was then busy painting, so I went to The Hague alone. The sittings took place in a castle in a forest, the queen’s residence, not far from The Hague’s city centre.

I had heard that Queen Beatrix was the most democratic of all the European monarchs and one of the richest women in the world. Before the sitting, I went to walk along the street named after Anna Pavlovna, the Russian grand duchess, daughter of Pavel I, and former Queen of the Netherlands. She was great grandmother of the ruling queen, making Russia’s Pavel I Queen Beatrix’s ancestor.

It was curious to talk to the queen about art and exhibitions, as I knew she was fond of sculpture. I remember her telling me about an exhibition of a Dutch female artist whom she loved and appreciated. The Queen had had to visit the exhibition secretly, at night. If she had attended the exhibition officially, it would have conferred popularity, a political mistake. How difficult the queen’s life is, and she has no one to complain to except a visiting Russian artist!

Norway

In 1998, while the King and Queen of Norway were visiting in Moscow, they went to the Kremlin Museum and saw my English miniatures. They agreed to sit for us, after which I.A. Rodimtseva arranged everything through the Norwegian embassy in Moscow, and I went to Oslo with Mr. Efros.

The "sitting" of the royal full dress uniform.

The Royal Palace. Oslo, 1999

We knew in advance that there would be no interpreter. Normally, people sitting for their portraits, silent and idle for a long time, find themselves working harder than the painter does or they start yawning. The queen had the foresight to ask her secretary to read her correspondence during her sitting.

When the king came in, however, the servants went away and we had to talk to him. We talked about Russia, about his visit to Moscow. The king was interested in how the sitting had gone in London. We regretted that he hadn’t worn his dress uniform.

The next day, the uniform “sat” for us alone. One of the guardsmen, much the same height and figure as the king, modeled it. Another person was also present to be responsible for the uniform’s safekeeping; he oversaw the guardsman in the uniform. The king could be alone in the room, but not his full dress uniform!

Epilogue

With time, these events have become history. Schoolbooks in the social sciences have published the beautiful “Portrait of Queen Elizabeth II” by Mr. Efros. I found an Internet link to the Russian record book “Divo,” which described our work in London as exceptional in their section “Art.” In a letter from my father in 2002, he wrote that radio “Mayak” had celebrated the tenth anniversary of the British Queen’s sitting for me in their rubric “Significant Events.”

Of all my portraits, I appreciate most my small miniature of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, which she autographed. She didn’t simply sign it; she traced out painstakingly, “Clarence House. March 31st 1992.” She died on the same day ten years later, 31 March 2002. The night before, she came to me in a dream, and in the morning, I learned from the Internet that Her Majesty was gone.